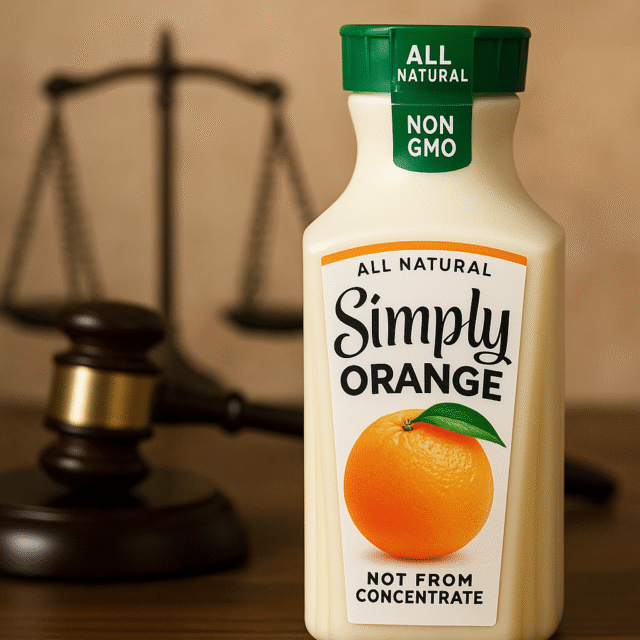

The simply orange lawsuit challenges Coca-Cola’s claims about its juice. Plaintiffs say Simply Tropical and other drinks contain PFAS. These chemicals are known as “forever chemicals.” They linger in bodies and the environment. The lawsuit argues that “all natural” labels misled shoppers. It also claims buyers paid more for a false promise.

Court filings began in New York. Judges reviewed evidence of testing. Early complaints faced dismissal over weak proof. Yet plaintiffs returned with stronger allegations. Coca-Cola continues to deny wrongdoing. The case now moves through motions and hearings. Its outcome could affect food labeling rules nationwide.

The Brand Behind the Case

Simply is a Coca-Cola company brand. It launched in 2001. It promised natural fruit drinks without additives. Consumers trusted its marketing. The word “Simply” suggested honesty. The design emphasized purity and freshness. The brand became a major juice player.

Orange juice is the flagship. Other drinks joined the line. Simply Tropical, Simply Lemonade, and Simply Apple hit stores. Each carried “all natural” imagery. Buyers paid premium prices. The brand held strong market share. Trust became its greatest asset. That trust now faces pressure.

The Lawsuit’s Origins

In December 2022, a New York buyer filed suit. His name is Joseph Lurenz. He purchased Simply Tropical juice. Independent testing allegedly revealed PFAS in that product. PFAS are often called “forever chemicals.” They stay in bodies and the environment.

The complaint claimed mislabeling. Labels promised “all natural” juice. The suit argued chemicals violated that promise. It said customers paid extra for purity and sought compensation for economic loss. It also asked the court to stop deceptive practices. The initial filing covered one product. It relied on a single lab test. That became a weak point. Courts require stronger evidence. The first judge highlighted the gap.

First Round in Court

The first major decision came in June 2024. The judge dismissed the amended complaint. He focused on standing. Standing means showing a personal, direct injury. The judge noted a single test sample. He said that one test did not prove contamination in plaintiff’s bottle. He required more evidence and allowed another chance. The dismissal came without prejudice. That meant the plaintiff could try again.

The order emphasized legal standards. It did not decide whether Simply products contained PFAS. It did not declare products safe or unsafe, it simply ruled that the complaint lacked specific proof.

Second Amended Complaint

In July 2024, a new complaint landed. This time it was far longer. It alleged broader contamination and claimed multiple tests revealed PFAS across Simply products. It expanded scope beyond Simply Tropical. The complaint included orange juice and lemonade. It alleged systemic issues, not isolated ones. It pointed to repeated “all natural” messaging. Also, it argued that Coca-Cola knew or should have known.

The new filing added class action details. It sought relief for all affected buyers. It asked for damages and label changes. The expanded narrative set up a stronger challenge.

Coca-Cola’s Counterattack

Coca-Cola responded in July 2024. It filed a new motion to dismiss. The company argued the complaint still lacked plausibility. It said testing failed to prove contamination across all bottles. Defense lawyers stressed consumer standards. They argued “all natural” does not equal PFAS-free. They said claims stretched beyond reasonable interpretations and warned that expanding labels could mislead in other ways.

The defense also challenged class certification. They argued individual purchase details varied. They said broad damages would be unfair. The motion framed the lawsuit as weak and speculative.

PFAS in Focus

PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. They include thousands of synthetic compounds. They resist heat, oil, and water and they persist in nature for decades. Some PFAS link to health risks. Studies show ties to cancer, thyroid issues, and immune effects. Exposure sources vary. Water, packaging, and household items often contain PFAS.

FDA has studied PFAS in food since 2019. It monitors packaging, cookware, and direct contamination. The agency tightened rules in 2024. Several PFAS used in grease-resistant coatings lost approval. This context frames the Simply case. Plaintiffs argue PFAS presence makes “all natural” misleading. Defendants say science does not justify blanket claims.

Marketing Under the Microscope

Simply built its image on natural purity. Ads highlighted fresh fruit. Phrases like “all natural” appeared everywhere. The plaintiff said these claims shaped purchase decisions. He argued that families trusted the promise and claimed they paid more believing the juice was chemical-free. He called this a price premium. The case hinges on that idea.

Defense lawyers counter that “natural” means minimal processing. They say no label guaranteed PFAS absence. They note that no law defines “natural” strictly. Courts must decide how a “reasonable consumer” interprets the phrase.

The Role of Standing

Standing remains the central hurdle. The judge pressed for personal injury proof. He said allegations must tie to actual purchases. One test sample did not link to Lurenz’s juice. The second complaint added more testing claims. It tried to show widespread contamination. It still faces challenges. Defense lawyers argue the gap remains. They stress that not all batches tested positive. Standing rules protect courts from abstract disputes. They require concrete harm. This principle will shape the next ruling.

FDA’s Influence

FDA actions weigh on the case indirectly. The agency has not banned Simply juices. It has not declared them unsafe. Its actions focus on packaging. In 2024 and 2025, FDA phased out grease-proofing PFAS. Food-contact approvals lapsed for dozens of chemicals. This shift highlights rising PFAS concern. It also shows regulators shaping future claims.

Courts may view FDA oversight as key. Defense may argue compliance with regulations shields Coca-Cola. Plaintiffs may argue that evolving science shows deception. The tug-of-war between law and policy continues.

Consumer Reaction

Consumers felt alarm when headlines spread. Many believed the suit targeted Simply Orange itself. Confusion grew between orange juice and Simply Tropical. Social media amplified fear. Some buyers boycotted the brand. Others demanded refunds. Many still purchased as usual. Supermarkets kept Simply drinks on shelves. No recall emerged.

Parents asked doctors about risks. Experts said context matters. PFAS exposure varies. Levels in a single juice may not equal harm. Still, trust matters. The lawsuit damaged brand reputation regardless of outcome.

Comparison to Other Food Lawsuits

The Simply case is not unique. Other brands faced PFAS suits. Cookware, bottled water, and fast-food packaging all came under fire. Courts dismissed some cases. Others advanced to discovery. Most claims focus on marketing language. Words like “natural,” “pure,” and “clean” often trigger disputes. Plaintiffs argue deception. Companies argue reasonableness.

Settlements sometimes follow. Labels change. Funds pay class members. These outcomes rarely decide broad scientific truth. They resolve legal disputes and restore market calm.

Possible Outcomes

Several outcomes remain possible. The judge may dismiss again. That would shrink the lawsuit. An appeal could follow. The court may allow discovery. That stage would test contamination claims deeply. Experts would debate methods and results.

Settlement remains likely. Companies often settle to avoid trial risks. A deal could include label tweaks and consumer refunds. Trial is the least common outcome. Few labeling suits reach juries. Yet Robi v. Merck shows exceptions exist. If this case survives motions, trial remains possible.

Consumer Guidance

Shoppers want clear advice. Right now, no recall exists. FDA has not banned Simply drinks. Health agencies have not issued warnings. Consumers who feel uneasy can choose alternatives. They can track updates through FDA releases. They can follow court calendars for rulings.

Documentation matters if joining a class. Save receipts and photos. Record purchase dates. Evidence supports compensation claims. Most importantly, balance fear with facts. Lawsuits allege, courts test, and science evolves. Avoid misinformation spreading online. Stick to reliable sources.

Timeline of Events

- December 2022: First complaint filed. Focus on Simply Tropical.

- June 2024: Judge dismisses amended complaint. Standing too weak.

- July 2024: Plaintiff files Second Amended Complaint. Scope expands.

- July 2024: Coca-Cola files new motion to dismiss.

- Late 2024: Briefing continues. Case remains pending.

- January 2025: FDA confirms PFAS packaging phase-outs.

- August 2025: Court has not ruled again. Case still active.

Broader Policy Impact

The Simply Orange case sits in a wider policy debate. PFAS regulation expands each year. State and federal agencies push stricter standards. Companies adapt supply chains. Labeling law may change too. Clearer definitions of “natural” could arrive. That would settle many disputes. Congress could step in. FDA could update guidance. Public trust depends on clarity. Consumers expect transparency. Lawsuits highlight gaps in communication. They pressure firms to speak plainly. Policy may follow legal pressure.

Final Thoughts on the Simply Orange Lawsuit

The simply orange lawsuit is still unfolding. The first complaint failed. A longer second complaint followed. Coca-Cola pushed back hard. Judges weigh standing, injury, and label meaning. FDA policy shifts add weight. Consumers remain alert. No recall exists. No safety ruling has arrived. The lawsuit centers on labels and economics. Yet trust remains fragile. Brands survive on trust. Courts decide whether that trust was broken.

The simply orange lawsuit reflects modern consumer law. It mixes science, marketing, and accountability. Its outcome will echo across the food industry. Buyers, companies, and regulators now watch the same courtroom.